How a single tweet crashed a stock market wonder

Good morning, London. Apologies for the delay. Wanted to check in with counsel. These $BUR guys sure do have a guilty look to them, don’t they? https://t.co/XffuPD04QK

— MuddyWatersResearch (@muddywatersre) August 7, 2019

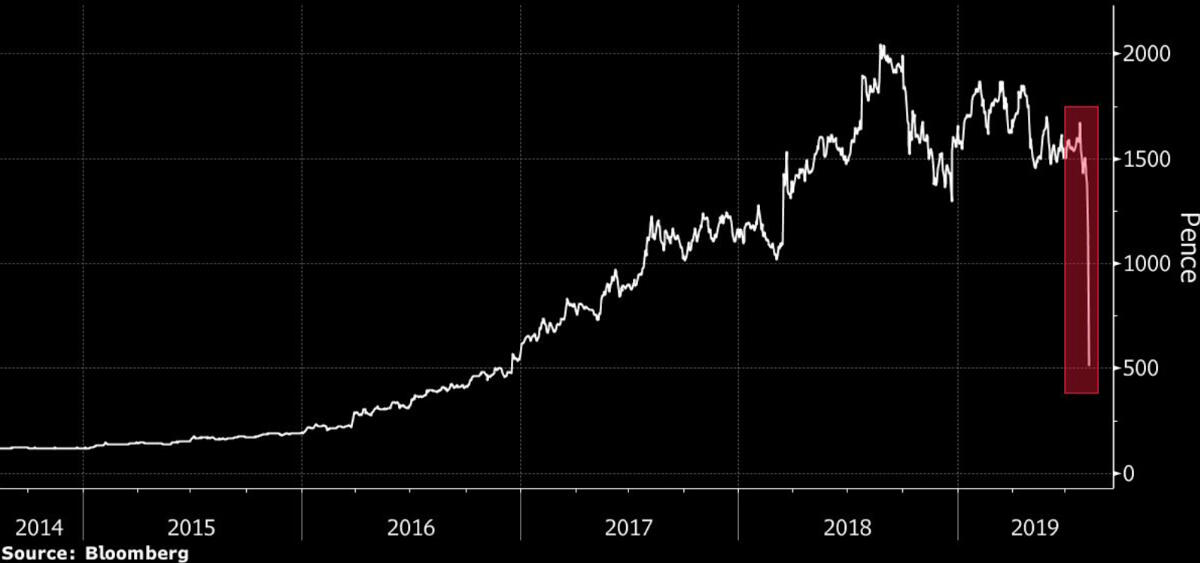

Over a dinner in 2009, as two old law school friends chatted about the problems with how legal cases were funded, a business idea began to form: in return for a portion of settlement or damages payments, a financing company could provide upfront funding for litigation. The potential market was huge.Ten years later, the company founded by Christopher Bogart and Jonathan Molot, Burford Capital, would have offices in New York, London and Chicago, and be worth more than £3 billion. ⁱThis unblemished success story ended in August 2019, with just a single tweet.Shortly after a mere 213 text characters entered the public domain, Burford’s market value collapsed at one point by as much as 72%. ⁱ It has never recovered to its previous levels.

The tweet ⁱ , posted by short selling hedge fund Muddy Waters, pointed to a carefully structured letter ⁱ raising questions about Burford’s accounting and governance. As such, it appeared to follow the standard activist short selling playbook.The market reacted fast. The fall in the price of Burford’s stock was staggering. To most people this appeared to exemplify the role well prepared investment research can play in suggesting problems with public companies.But this explanation is unable to account adequately for why that single tweet was so devastating. It cannot explain the velocity at which Muddy Waters’ investment case permeated the media and the investment community. Most importantly, it can't describe why that investment case was promulgated completely intact and with such longevity that it is so immediately recalled to mind nearly a year later.The answers to these questions are not just relevant to, but absolutely essential for all businesses, organisations and individuals that operate in the public eye. Furthermore, they make salient the critical importance of a new form of analysis and corporate intelligence - the interplay and co-dependence of networks and narratives, and a new discipline - navigating them.

Introducing a new form of corporate intelligence

In a series of three short articles, the Rebbelith team will tell an exciting but important story - a story of how a network of ‘narratives’, some of which were formed decades before Burford existed, combined with an information network to set in motion a chain of events that accelerated and embedded Burford’s crisis and created a kind of communications ‘checkmate’.The first article will introduce the communications challenge posed by investing in esoteric assets. It will then demonstrate the three key, avoidable reasons for why Burford’s communications advisers and publicity agents failed that challenge:

They lacked the technology needed to identify and address the themes in investor-valued media that actually grew around the company. These became embedded and created critical ‘narrative vulnerabilities’.

Some of Burford’s crucial investor messages did not successfully form part of its growth narrative in key investor media because of misjudged announcements and inadequate content.

The company lacked the technology required to identify the media and journalists that were actually valued by its investors.

Figure 4 from series Part One: ‘Pioneers and Complexity’. Mapping the publications and journalists most valued by Burford’s key investors in the summer of 2019

The second article will reveal two dimensions beyond the simple activist short selling playbook that made Muddy Waters’ attack so effective:

Muddy Waters identified the incredible power of the narratives contained in, orbiting or connected to Burford. They were capable both of realising their individual communications potential and of linking them together to create an inescapable ‘narrative entanglement’.

They had a detailed appreciation of how information networks behave and the different ‘message carrying’ characteristics of particular media channels.

Figure 2 from series Part Two: ‘The Attack’. Creating ‘narrative entanglements’ - invoking Enron as supporting narrative

The third and final article will explore why Burford’s responses were ultimately ineffective. It will then show how a modern, data-backed approach to communications could have helped. These themes will be discussed in three assessments and one suggestion:

Burford’s admirable but ultimately ineffective technical rebuttal - released the day after the attack.

The significant but squandered opportunities contained in the ‘spoofing and layering’ counter narrative the company launched.

How the ‘communications checkmate’ affected further responses.

Suggesting a modern, data-backed and visual approach to building an effective communications strategy for an investor facing business.

Figure 2 from series Part Three: ‘Checkmate’. Burford’s August 12th ‘Spoofing and Layering’ counter narrative - potential to escape ‘checkmate’

The importance of networks, narratives and navigation

Through these three articles we will show why narrative and network intelligence must become an integral part of reputational, brand and communications strategies for every organisation. Like the original Rebbelith maps from which we draw our heritage, we will explain how the media and stakeholder discussions that occur in the modern world can now be charted and navigated confidently.

Next time...

In Part One: Pioneers and complexity, the Rebbelith will reveal the three key, avoidable reasons for why Burford’s communications advisers failed the communications challenges of investing in esoteric assets.The article will show readers how ‘narrative vulnerabilities’ began to grow unchecked around the company, and it will explain why some of Burford’s investor messages didn't end up forming part of its growth story.Finally, Rebbelith will assess Burford’s media outreach strategy to show how much potential value could have been realised by their communications advisers.

Part One - Pioneers and complexity

How a single tweet crashed a stock market wonder

In August 2019 a stock market wonder crashed following just a single tweet. The valuation of the company, Burford Capital, has never recovered to its previous levels following the attack by activist short selling hedge fund Muddy Waters.This is the first in a trilogy of articles produced by the Rebbelith team exploring that attack and why the reasons for its success are so important to all communications experts, reputation managers and brand strategists who operate or serve clients in the public domain.

Narrative vulnerabilities, investor messages and valued media

Burford’s story was really compelling, both for clients and for investors seeking sources of income uncorrelated to traditional markets. The company’s founding idea, potential market and legal experience provided them, their communications advisers and publicity agents with the immediately clear, enviable ‘early mover’ narrative that few businesses are lucky enough to enjoy. They were ‘pioneers’.But Burford invested in esoteric assets. These were difficult to value, the timing of future cash flows was hard to predict and the nature of litigation itself was complex. Compared to that ‘pioneering early mover’ narrative this aspect of the business was not immediately clear. Only a small number of people with specialised knowledge would likely understand the litigation process and its potential financial value. For a publicly listed company subject to standardised reporting and public scrutiny this made explaining Burford’s ability to deliver reliable value into the future a serious communications challenge.It was absolutely imperative that this challenge be met - as Muddy Waters would later reveal, that degree of complexity significantly raised the potential for confusion and for vulnerable narratives to grow around the company.

This article will explore the three crucial and avoidable reasons for why Burford failed this challenge:

It lacked the technology needed to identify and address the themes in investor-valued media that actually grew around it. These became embedded and created critical ‘narrative vulnerabilities’.

Its stated investor messages did not successfully form part of its growth narrative in key media. This was due to inadequate amounts of relevant content, to certain data it continually provided, and to some of the announcements it repeatedly released on the London Stock Exchange Regulatory News Service (RNS). Those announcements did not align with its investor messages and in one area significantly diluted them.

It lacked the technology required to identify the media and journalists that were actually valued by its investors. It instead deployed an unimaginative outreach strategy focussed on legal trade publications, and it relied too much on the scattergun reach of the RNS. Most importantly, poor monitoring of the right media meant harmful narrative vulnerabilities grew unchecked.

Had Burford deployed modern, data-backed media and narrative analyses rather than old, legacy strategies, these failures would have been conspicuously avoidable.

Reason One: Burford failed to monitor its narrative vulnerabilities

Media described Burford’s growth and rising share price by repeatedly covering specific themes. But whilst these themes helped drive the Burford success or ‘growth’ narrative, they also embedded vulnerabilities within it, later to be levered or ‘activated’ by the Muddy Waters attack and its highly sophisticated communications campaign. The story of these narrative vulnerabilities, how they grew within media coverage, what caused them and the way in which they were ignored, is told below through three key examples.

A focus on single large investment cases

Media referenced single large investment cases in Burford’s portfolio again and again. Retail investor publications actually used these single cases to justify buy recommendations. Others leant on them to frame the exciting and increasing growth of the business.One case exemplifies this. In 2017 retail investment publication Investors Chronicle covered Burford’s “thumping” pre-tax profit for the 12 months ending December 2016. This was 28% above ‘consensus estimates’. Within that review the high price of Burford shares was specifically justified through the company’s interest in a single large investment case, the ‘Petersen’ claim. That interest, it claimed, was worth more than three times the company’s profits in 2016.Again in 2018, the Petersen claim was used to “put the scale of the (Burford’s) undervaluation into perspective” ⁱ by one reporter, who subsequently revealed analysts at broker Liberum believed the company’s stake in the claim could be worth as much as $1.12bn.The reasons for successive coverage like this were logical and simple - media intuitively picked up on the most noteworthy announcements from the company or the things they chose to highlight in content.But this also meant that readers were continually exposed to the significance and publicity media gave those single large investment cases. Over time this repetition meant those single cases became a key aspect of Burford's growth narrative and a key driver of its share price.

Returns Metrics

Investor-focussed media continually referenced the high Internal Rates of Return (IRRs) and Returns on Invested Capital (ROICs) reported by Burford over the years to describe its financial performance. Mention of these metrics came, firstly, alongside narratives of how the company had moved the litigation finance industry from ‘niche’ to ‘mainstream’ and, secondly, how that industry was “exploding”.Continued media references to these IRR and ROIC metrics served to support Burford's profitable ‘early mover’ role in those industry narratives. Their repeated presence in media coverage also helped to verify readers’ beliefs in Burford’s potential value, and offered a way of quantifying those beliefs simply.But their effectiveness in verifying those beliefs had a hidden and increasing narrative cost. Like the successive reference to single large investment cases to describe the company’s potential, continued media citation of unreliable IRR metrics meant they too became embedded in Burford's growth narrative.

Unrealised gains

Without a careful strategy to guide investors there was potential for the complexity of the company’s valuation methods to become confusing or misunderstood. Even worse, they might be criticised publicly.Because of the very specific nature of litigation, Burford attributed value to its ongoing investments in legal cases according to a process known as ‘fair value’ accounting. This meant they increased or decreased investment values based on objective events in the progress of the litigation, rather than recording profits after the conclusion of a legal case and the final receipt of cash. This process resulted in ‘unrealised gains’ being recorded in the company’s accounts.In their 2014 annual report Burford showed how the level of unrealised gains remained the same as the previous year, at 11% of assets. That report described their valuation methodology as ‘conservative’. Investor media duly lifted this figure and message of ‘conservatism’ straight from the report.Over the next few years, as Burford’s growth narrative developed alongside its share price, and as it ploughed more and more cash into new legal investments, reporters acknowledged the increasing level of unrealised gains. But they did so only as references, as ‘backstage asides’ nestled amongst endlessly positive analyst estimates, coverage of staggering profits, and high IRRs. By 2018 the share price was being termed “meteoric”, and the company described as “undervalued”. ⁱ ‘Unrealised gains’ themselves received little specific media attention.But this lack of explanation made Burford vulnerable.

Figure 1: Media described Burford’s growth and rising share price by repeatedly covering specific themes. But whilst these themes helped drive the Burford success narrative, they also embedded vulnerabilities within it.

Reason Two: Burford's content was inadequate and its messages were confusing

Single large cases dilute diversification message

Part of Burford’s investor message attempted to make clear that its investment portfolio was both large and diversified. Its investor materials, like annual reports, discuss this ⁱ .

"Part of the secret of litigation investing is having a large, diversified portfolio"

- Burford Annual Report 2017

"Burford’s financial performance is the product of many investments”

- Burford Annual Report 2017

The successful permeation of this message throughout its growth narrative would demonstrate an ability to generate income smoothly and predictably. This would help to retain existing investors, attract larger ones and thus reduce volatility in its share price.But ‘diversification’ did not adequately permeate media coverage. It did not form a meaningful part of the company’s growth narrative in key publications. Instead, reporters focused on the huge value of single large investment cases. This happened for two reasons - inadequate content and the choice of announcements.

Inadequate content

The company’s communications strategy failed to back this diversification message with newsflow or content that demonstrated it effectively and carried it to the most valuable media. Untargeted RNS announcements, articles in niche legal trade publications and infrequent annual reports were simply inadequate tools for embedding such an important message within that audience over time. There was also insufficient acknowledgement or repetition of this essential message in the required investor materials - the company’s 2014 annual report even delegates finding details of portfolio diversification to the reader:

"We also won’t repeat in any detail our devotion to the construction and management of a large and diversified portfolio of litigation investments, but we believe that is a critical way to go about investing in this asset class, as each investment comes with idiosyncratic risk that can only be properly managed through diversification." ⁱ

If it was critical, management should have been discussing portfolio diversification actively - their media team should have advised them to do so, identified suitable media opportunities and produced content around it for targeted distribution through the company’s social media assets.

Choice of announcements

Some content Burford announced to the market repeatedly highlighted the significance and huge potential future value of single large investment cases rather than the merits of a diversified portfolio. On two occasions announcements highlighting the possible values of such cases were made just before or in conjunction with major financial results.On the 14th March 2017 at 07:00, just one minute before the previous financial year’s full results were released, Burford announced the partial sale of interests in a single investment - ‘the Petersen Claim’. The sale implied “a market value for the investment of $400m.” ⁱIt is very possible such announcements altered the way aggregate financial results (required by market regulations) would have been interpreted by anyone reading them: it is plausible those announcements may have ‘primed’ readers to note particularly the importance of single large investment cases as they made or confirmed their own ideas of Burford’s value potential.The next year Burford repeated this announcement pattern. On 13th March 2018, on the day immediately before the 2017 full year results were released, the company announced it had sold its entire interest in a single arbitration case called ‘Teinver’. The announcement was titled `“BURFORD SELLS TEINVER INVESTMENT FOR $107 MILLION, A 736% RETURN” ⁱThese messaging decisions increased positive analyst estimates, but at a real cost. They diluted the impact of any attempt to create a narrative around portfolio diversification, and they helped embed single large case successes within the Burford growth narrative.

Returns metrics

It was a challenge for Burford to identify the right metrics with which to describe its profitability. The timing of its cash flows was difficult to predict and its assets were hard to value with traditional, common methods. This meant standard metrics were unsuitable.Indeed as early as 2013 and 2014 the company’s annual reports clearly stated the company’s reluctance to use IRRs to measure its profitability or the performance of its investments reliably:

“We are often asked about IRRs. Particularly given the multiple lines of business in which Burford is now engaged and the widely varying nature of our investments, we regard IRRs as a less helpful measure than return on invested capital (on a per investment or portfolio basis) and return on equity (for the entire business). That is especially true when one considers that we have one matter with IRR in excess of 15,000%, another in excess of 1,000% and several more well into the hundreds – but that does not necessarily signify that those were fantastic investments (although we were perfectly happy with them) because we can’t reliably put out capital in our business repeatedly and have it returned as quickly as occurred in those matters. Indeed, as a general matter, we would have preferred our capital to be outstanding for longer in those ultra-high IRR matters, so that we generated greater cash profits but lower IRRs.”

- Burford Capital 2013 Financial Report ⁱ

“NAV and IRRs are not the appropriate valuation metrics for this business, as the research analyst community increasingly recognises.”

- Burford Capital 2014 Financial Report ⁱ

But these metrics continued to be provided by Burford over the years. Inevitably, they were included in media coverage of the company’s share price potential. And whether unintentional or not, this meant potentially unreliable metrics became steadily, cumulatively inseparable from the company’s success story, and Burford’s IRRs became embedded in its growth narrative.

Unrealised gains

Various investor-valued media mentioned the growing unrealised gains on the company’s balance sheet over the years. As discussed, they did so mostly in a benign manner and as casual references. But these references didn't echo an adequate set of defined, simple and crystal clear company messages, and this meant the company’s valuation methods weren’t explained to or familiarised with investors through key media.Those media could have provided a powerful third party validation for these messages and that explanation. They could have improved its familiarity with target audiences and thus reduced the potency and newsworthiness of potential future criticism. But these simple messages did not permeate media successfully for two key reasons:

The content used to carry them was inadequate or confusing

The company mainly discussed its complex valuation methods as part of announcements on the RNS and in annual reports. This required significant active searching by readers and limited message frequency to a few pieces of content.The messages in those announcements were also inherently confusing and inconsistent. They appeared to imply values for single large investment cases but then immediately introduced caveats, stating they did not “necessarily regard the implied valuation of these sales as the appropriate carrying value for the remainder of the investment on Burford's balance sheet.” ⁱ These lengthy explanations of complex valuation methods were just copied and pasted from page 23 of the 2016 Annual Report. ⁱ This same messaging confusion occurred in announcements made on 14 March 2017 ⁱ, 13 June 2017 ⁱ, 24 July 2017 ⁱ and 13 March 2018. ⁱ

The company failed to recognise a lack of explanation in key media

Burford’s lack of awareness (and certainly lack of action) with respect to how media covered unrealised gains meant they couldn't guide the existing discussion or recognise potential future vulnerabilities in coverage.As investor appetite for Burford continued, in January 2019 the publication ‘Investors Chronicle’ ran a story on the future of litigation finance. That article discussed a failed IPO by Burford peer ‘Vannin Capital’, and demonstrated how hard it could be to convert such esoteric investments into hard cash.Then, amongst media reviews in March 2019 of the previous year’s results, after years of continued share price growth, it was mentioned that ‘unrealised gains’ now accounted for more than half (55%) of Burford’s reported income. More importantly, reporters were starting to include this in bearish ideas, possibly signifying that a negative narrative of ‘opacity’ and ‘complexity’ was present. But Burford had left it too late to communicate its valuation methods clearly enough, and over enough time.In June 2019 hedge fund Gladstone opened a short position in Burford Capital equivalent to 0.5% of the outstanding shares. It was suggested that the company had inflated its past returns on ‘unrealised’ investments. “Burford’s business”, said one publication, _“requires a lot of trust in management.” _ⁱ

Figure 2: Inadequate content and poor messaging meant ideal investor messages (green) were not carried through to media. This meant narrative vulnerabilities (red) became embedded in the company’s growth narrative (grey) over time.

Reason Three: Burford failed to identify the media and journalists that were actually valued by its investors

Burford’s main shareholders included some of the asset management industry’s leading funds.

| Fund | Portfolio Holding % | As at (date) |

|---|---|---|

| Woodford Equity Income | 5.8 | 30/04/2019 |

| Mirabaud UK Equity High Alpha | 4.0 | 28/06/2019 |

| Invesco High Income | 3.9 | 30/06/2019 |

| Edinburgh Investment Trust | 3.7 | 30/06/2019 |

| Omnis Income & Growth | 3.2 | 28/06/2019 |

| SVM UK Growth | 2.6 | 30/06/2019 |

| Jupiter Absolute Return | 1.9 | 30/06/2019 |

| Aberdeen Diversified Income | 1.7 | 30/06/2019 |

| Aberdeen Diversified Growth | 1.6 | 30/06/2019 |

Source: fund factsheets

Figure 3: Key Burford shareholders (summer of 2019)

The company could have signalled its key investor messages to its main shareholders continuously if it had received adequate insight from its communications strategists and publicity agents. With such insight, the company could have determined:Firstly, which publications and individual journalists had the most reach with those key shareholders.

Figure 4: Mapping the publications and journalists most valued by specific investors

Secondly, the individual reach of those publications or journalists.

Figure 5: Revealing the reach of specific journalists or publications

Thirdly, the media most valued by each key shareholder.

Figure 6: Publications and journalists most valued by individual investors

Fourthly, the company could have built an investor relations campaign with accurate knowledge of its true, valued-media landscape, and accurately monitored those titles and journalists for the growth of narrative vulnerabilities.

Figure 7: Burford’s key investor media landscape

Burford instead pursued an antiquated, legacy media targeting strategy focussed on legal trade publications and reliant on the scattergun reach of the London Stock Exchange Regulatory News Service (RNS).Huge opportunities to ‘signal’ Burford’s value and embed its key investor messages, over time and in the optimum investor-valued media, were wasted.

Figure 8: Burford media team’s publication focus January 2017 - August 2019 (larger nodes denote publications with the greatest focus)

From October 2015 to the end of July 2019, Burford focussed attention on a few small, niche legal trade publications, likely identified by its communications advisers through generic searches for ‘law’ and ‘trade’ on aging media databases. Its forays into valued business media were sporadic and unsustained. Its use of Bloomberg’s powerful newswire remained mostly relegated to its law desk.Even in these unsuitable media, the thematic focus of outreach by Burford’s media team was misguided. The only themes that received concerted publicity effort were the growth of the litigation funding market, and accompanying comment. During a period of rapid share price growth between the summer and autumn of 2017, discussion of single large investment cases also saw focus by that media team.But, and even in these unsuited media, it's the absence of one theme and the timing of another which suggests the company’s communications strategists were ill informed. Firstly, essential discussion of portfolio diversification and valuation methods occurred sporadically and very infrequently. Secondly, as bearish ideas spread through investor media in the summer of 2019 and Gladstone opened its short position, the company was focusing media resources on gender equality rather than investor communication.

Figure 9: Thematic focus of outreach by Burford’s media team (May 2017 - August 2019)

This outreach pattern may have been thought adequate for a broad targeting of potential customers or clients. But, and so crucially, it neglected how critical the right media are to achieving successful investor communications, for signalling value sustainably, and for monitoring the development of narrative vulnerabilities.

Next time...

In the second article, the Rebbelith team will explore the structure and dynamics of the attack itself to reveal its two unique dimensions. It will show how these went beyond the simple activist short selling playbook and made Muddy Waters’ attack so effective.Through new narrative and network maps, readers will be taken through a visual journey of what happened, what a ‘narrative entanglement’ looks like and why an understanding of them and networks are so important to businesses and individuals in the modern public domain.

Part Two - The attack

How a single tweet crashed a stock market wonder

In August 2019 a stock market wonder crashed following just a single tweet. The valuation of the company, Burford Capital, has never recovered to its previous levels following the attack by activist short selling hedge fund Muddy Waters.This article is the second in a trilogy exploring that attack. Through new narrative and network maps, readers will be taken through a visual journey of what happened. They will see what a ‘narrative entanglement’ looks like and gain an understanding of why they and information networks are so important, both to communications experts and reputation managers, but also to all brand strategists.

Narrative entanglements & information networks

At first glance the attack on Burford was one dimensional. It appeared simply to follow the activist short selling playbook. This prescribes the public questioning of a company’s accounting practices, its governance and its valuation to stimulate a correction in its share price by exposing ‘true value’ to the market.But the Muddy Waters campaign included two further dimensions which this article will reveal and explore.

It understood the incredible power of the narratives contained in, orbiting or connected to Burford. It was capable both of realising their individual communications potential and of linking them together to create an inescapable ‘narrative entanglement’.

It had a detailed appreciation of how information networks behave and the different ‘message carrying’ characteristics of particular media channels.

It is these dimensions that make this campaign such an important lesson for brand strategists, corporate communications teams and reputation management experts operating in all areas of business.

Dimension One: Creating a narrative entanglement

Muddy Waters linked ‘idiosyncratic’ narratives - those which were a direct product of Burford and its growth story - with embedded or ‘supporting’ narratives - famous scandals that provided ‘shorthand’ descriptions to give the attack historical precedent and perceived significance.These links created a network of narratives that surrounded and ‘entangled’ the company, limited its ability to respond effectively and guided almost all of the future media debate.

Idiosyncratic narrative 1: The ‘wonder stock’ - inverting a success story

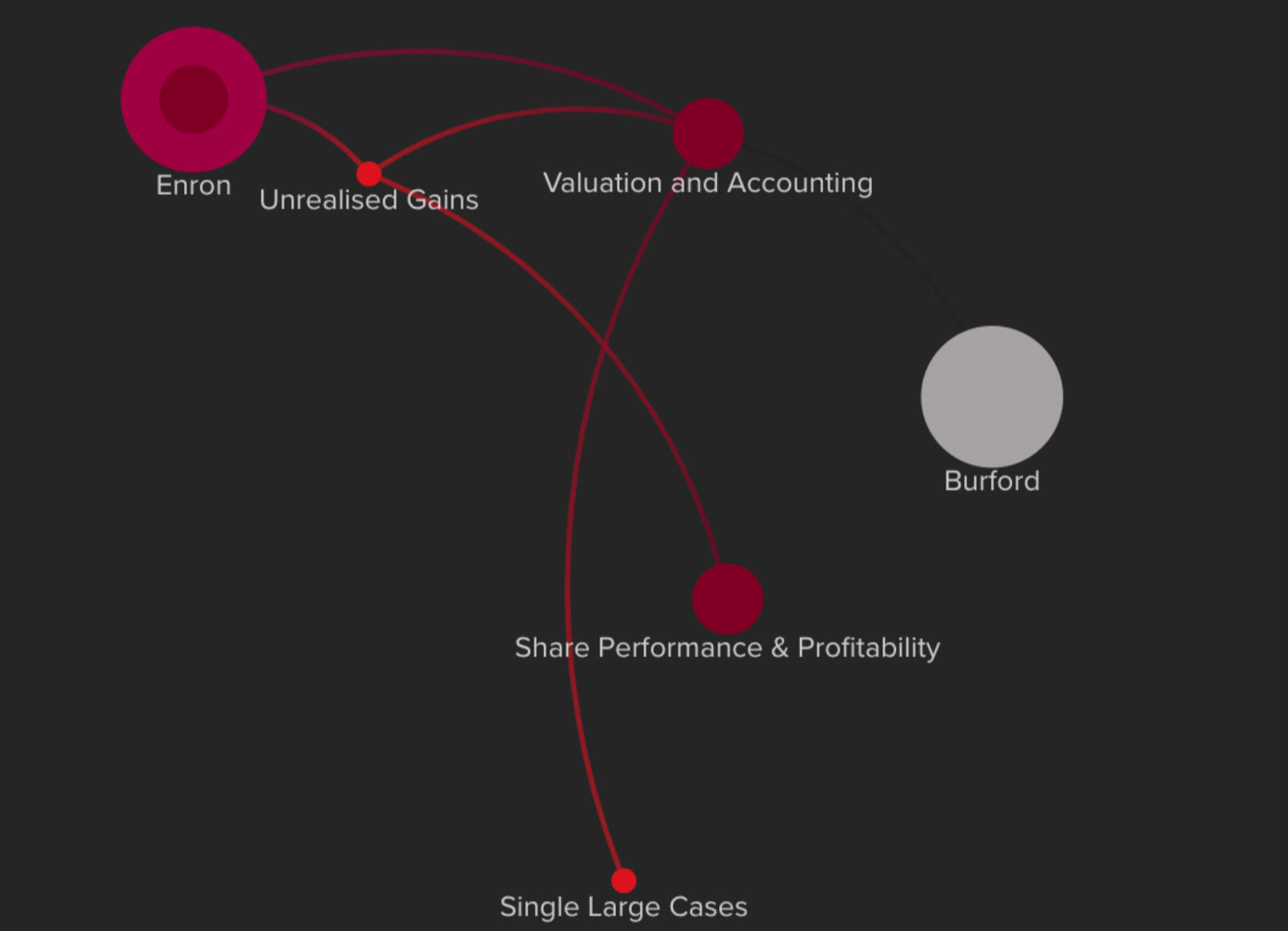

Muddy Waters described Burford as “the biggest stock promotion on AIM”.The previous article explored the effect of recurring media themes on the company’s growth ‘narrative’. These included the repeated coverage of inappropriate IRR metrics and the focus on single large investment cases. It showed, firstly, that whilst these themes helped drive the Burford success story and its share price they also embedded vulnerabilities within it and, secondly, that a communications strategy should and could have identified their presence and the narrative vulnerabilities they presented.

Figure 1: Narrative vulnerabilities in Burford’s share price and profitability (idiosyncratic narrative 1)

It was these same recurring themes that Muddy Waters highlighted so successfully to raise doubt about the company’s valuation, its profitability and even the viability of its business model. This actually ‘inverted’ Burford’s share price success story to reveal powerful narrative vulnerabilities. These were then ‘supported’ by invoking famous scandals to add context and contagion to the attack. One of these scandals occurred 19 years ago. Another was just peaking in the summer of 2019.

Supporting narrative 1: Enron - increasing contagion and perceived significance

Muddy Waters’ letter invoked the Enron scandal to support its interpretation of Burford’s accounting methods. This increased the penetration and spread of those core attacks in media. It also gave them a perceived ‘narrative heritage’ or ‘precedent’.This is because Enron is a household story. It contains an established narrative that still serves as a shorthand description for fraud conducted knowingly, at scale and with a high level of complexity. The Enron narrative unfolded nearly two decades ago but invoking it immediately transported anyone reading the letter (including the media) to that story, and it framed how people interpreted Muddy Waters’ claims around Burford’s accounting. It is a well-paved ‘memory highway’ to a whole event - to a whole narrative.

Figure 2: Invoking Enron as supporting narrative (supporting narrative 1)

Idiosyncratic narrative 2: Corporate connections and investors

Muddy Waters drew specific attention to Burford’s relationship with two of its key investors. Specifically, their attack suggested links between one of these and the success of a single large investment case.This connected narrative vulnerabilities in Burford’s growth story - ‘unrealised gains’ and single large investment cases - to the company’s corporate connections and investors. To raise contagion and add a narrative support, it then tied these connections to a major scandal that was dominating financial and investor media.At the time of the attack, two of Burford’s largest shareholders were funds run by Woodford Investment Management Ltd and Invesco Asset Management Ltd.Muddy Waters claimed that a fund run by Invesco’s Mark Barnett helped a US biotech company, Napo Pharmaceuticals, to repay money owed to Burford from a legal case. The Muddy Waters letter ⁱ described this as a “bailout”, without which the case - a significant contributor to net revenue booked by Burford - would have been loss-making. ⁱ

Figure 3: Linking key investors to narrative vulnerability ‘single large cases’ (idiosyncratic narrative 2)

This again highlighted the importance of single large cases in order to question the viability of Burford’s business model. But it simultaneously questioned the role the company’s investors played in these cases and, just as importantly, highlighted potentially problematic corporate connections.By specifically targeting the role played by Invesco and Mark Barnett, Muddy Waters also drew attention to a man who had initially invested in the company during its 2009 IPO when he himself worked at Invesco. This man was Neil Woodford.

Supporting narrative 2: The Woodford Scandal

Neil Woodford was undergoing his own scandal and liquidity crisis in the summer of 2019. Even before this scandal he was a household name in investing. But this changed when a significant liquidity mismatch emerged between what his firm invested in and the redemption terms that were granted to investors. This caused a public scandal that fuelled media interest for months and placed the asset management industry itself under scrutiny.Muddy Waters’ attack was launched at almost the optimum point in time to coincide with an exponential increase in media interest around Woodford.

Figure 4: Invoking the Woodford Scandal as supporting narrative: Muddy Waters’ attack was launched at almost the optimum point in time to coincide with an exponential increase in media interest around Woodford. (supporting narrative 2)

It linked Burford to the investment manager not just through financial connections, but by using the very potent and contagious narrative that was unfolding around it - a narrative of deception, opacity, complexity and risk to normal peoples’ savings. Even Burford itself suggested Woodford’s name had been included in the letter “for headline value”. ⁱ

Idiosyncratic narrative 3: Corporate governance - The CEO’s wife and board tenure

Muddy Waters described Burford’s governance structures as “laughter inducing” ⁱ . To justify this claim it made several key observations.It highlighted that the finance director at the time was married to the chief executive. This, the report said, was “unforgivable” at a company that records non-cash accounting profits and that “the very least the company could do is have an independent CFO.” It also observed that from 2010 to 2019 Burford had changed its finance chief four times. Furthermore, the attack claimed that, because its directors had sat on its board for around ten years, they were no longer independent under the UK corporate governance code.

Figure 5: Corporate governance connected to the CEO’s wife and the tenure of the board (idiosyncratic narrative 3)

Supporting Narrative 3: ‘appropriateness of AIM listing’

The attack also drew attention to Burford’s listing on the London Stock Exchange junior Alternative Investment Market (AIM) index. The company’s market capitalisation was large compared to its AIM peers, and the attack described it as a midcap firm. It questioned whether the company’s disclosure requirements were lighter than they would have been for the main market.This small reference raked up embedded negative commentary about ‘light touch’ regulation on AIM said to help the junior market attract pioneers and entrepreneurs from around the world without burdening them with costly red tape. This had led to the market being likened to the financial ‘wild west’ ⁱ .It was a reputational link that Burford could have done without, and the narrative effectively raised the contagion and perceived implications of the attack’s claims around corporate governance.

Figure 5: The company’s market capitalisation was large compared to its AIM peers, and the attack described it as a midcap firm. It questioned whether the company’s disclosure requirements were lighter than they would have been for the main market. (Supporting narrative 3)

Burford’s narrative entanglement

When combined, these idiosyncratic and supporting narratives were devastating. Their newsworthiness, coordination, depth and variety placed Burford in a narrative ‘entanglement’.

Figure 6: Mapping narrative networks - understanding Burford’s narrative entanglement

Dimension Two: A modern use of information networks

‘Priming’

Muddy Waters demonstrated a modern understanding how information networks behave. On august 6th 2019, the day before their attack was launched formally on twitter, they ‘primed’ their social media network to receive new information with a clear signal.

Muddy Waters is now in a blackout period until tomorrow 8 am London time when we will announce a new short position on an accounting fiasco that’s potentially insolvent and possibly facing a liquidity crunch. Investors are bulled up about this company. We’re not.

— MuddyWatersResearch (@muddywatersre) August 6, 2019

On 7th August the key tweet launched the attack fully, activating the narrative entanglement and levering the hedge fund’s significant social media network reach.

‘Pulsing’

Muddy Waters then raised the impact of the attack still further. In the hours and days after the initial attack they ‘pulsed’ slightly different messages through different media channels sequentially, all supported by the narrative entanglement they had created. These ‘pulses’ kept the attack fresh for three reasons:

They each included slightly different content.

They understood and used the different time span of messages carried by different channels, such as broadcast (more acute), and print (more chronic).

They were sent through channels with the most reach with key investors.

Static network ‘potential’

Muddy Waters recognised the enormous value of developed social media assets. Its twitter account functioned at a distribution capacity comparable to a fully fledged specialist financial newspaper. Its static network alone was over double the size of London daily paper City A.M., three times that of Financial News and over six times larger than FT Adviser or Citywire.

Figure 7: Static network ‘potential’: Muddy Waters’ twitter account functioned at a distribution capacity comparable to a fully fledged specialist financial newspaper.

The hedge fund’s social media relationships with the journalists and publications most valued by Burford’s key shareholders were also strong.

Figure 8: Mapping the attacks instant reach to publications and journalists valued by Burford’s key shareholders.

Muddy Waters’ initial content was instantaneously received by 18 of those 63 titles or commentators, and they would subsequently reach more.

Figure 8 (continued)

Burford’s underdeveloped social media assets did not intersect with investor-valued journalists or titles at all.

Figure 9: The result of Burford’s undeveloped social media assets: no intersections with investor-valued journalists or titles at all

Network depth and maturity

The investment community orbiting Burford was highly interconnected. That network also had significant overlap with Muddy Waters. This allowed information to spread rapidly and organically between those investors and their wider connections. The neglect of Burford’s social media network development meant there was very minimal overlap between the company, their investors and the wider investment community.

Reflections

Burford’s media team or advisers displayed neither awareness nor the presence of a strategy built upon adequate analysis, and were thus forced into a communications ‘checkmate’ by a narrative entanglement.Their attacker also understood how information flows in the modern media environment, how networks behave and the different characteristics of various media channels. They fully appreciated the importance of developed, high quality social media assets and used them to their potential.

Next time...

The next and final story will reveal the effects of this attack, the inadequacies of legacy communications practices in the face of modern communications campaigns, and the constraints it placed on Burford’s ability to respond.

Part Three - The communications ‘checkmate’

How a single tweet crashed a stock market wonder

In August 2019 a stock market wonder crashed following just a single tweet. The valuation of the company, Burford Capital, has never recovered to its previous levels following the attack by activist short selling hedge fund Muddy Waters.This article is the third and final in a trilogy exploring that attack and the crucial lessons it offers to all communications experts, reputation managers and brand strategists who operate or serve clients in the public domain.

Introduction

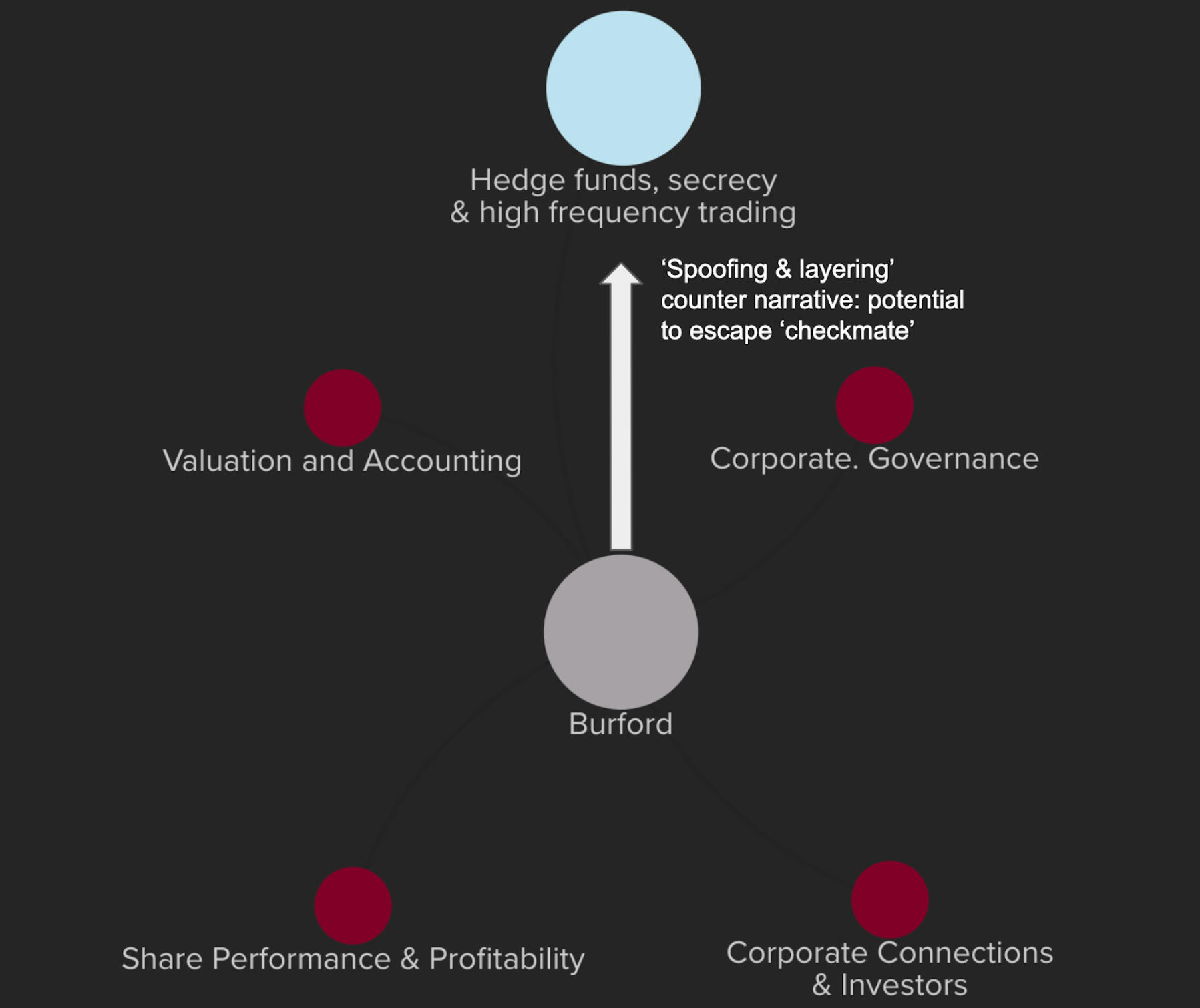

The Muddy Waters campaign in August 2019 penetrated the media incredibly effectively. This is because it harnessed two powerful dimensions beyond the simple activist short selling playbook: in the previous article, the Rebbelith team showed how it activated a network of stories or ‘narratives’ orbiting and connected to Burford, or contained in its growth narrative. It also levered the potential of modern information networks.The core components or ‘messages’ of that attack were indeed complex. But this narrative network meant that the complexity was described simply enough for a large audience. It also meant each component was reinforced by a ‘supporting narrative’. These added contagion and velocity to the overall campaign, and helped each message permeate the media intact and undiluted. This was a notably impressive communications achievement.However, the network also had a secondary, powerful and lingering effect. The combination of narratives it deployed created an intuitive story so well structured that it framed the media debate around Burford and its reputation.This ‘narrative entanglement’ formed a ‘communications checkmate’. It ensured responses launched by the company were restricted to operating within the narratives deployed against them. These constraints prolonged the life of these narratives for nearly a year.

Figure 1: The ‘communications checkmate’ - Burford’s ability to respond was constrained.

In this final article, the Rebbelith team will:

Address Burford’s admirable but ultimately ineffective technical rebuttal released the day after the attack.

Explore the significant but squandered narrative opportunities contained in the ‘spoofing and layering’ counter narrative the company launched.

Examine how the ‘communications checkmate’ affected further responses.

Suggest an alternative and modern approach to building an effective communications strategy.

Response One - the Rebuttal

To its credit, just one day after Muddy Waters tweeted, Burford released a forceful rebuttal ⁱ of the attack. This was a technical counterargument premised upon revealing “factual inaccuracies, simple analytical errors and selective use of information” in the Muddy Waters claims. It focussed on addressing the company’s solvency, strong cash flow and low debt levels, asserting the appropriateness of its accounting and reporting, explaining that its governance structure was robust and declaring the company was actively considering investor feedback. It dismissed “inflammatory rhetoric” and subsequently assessed each of Muddy Waters’ claims one by one. The document was well received by many investors. A fund manager at Jupiter Asset Management described it as “the best rebuttal to a short attack I’ve ever seen.” ⁱBut the riposte followed the tired financial PR crisis communications textbook to the letter. It was also nine pages long. Most significantly, it didn't introduce an adequate counter narrative. Doing so could have driven the strength of its technical arguments more effectively into media coverage and embedded them in the public mind. Crucially, it could have set the company’s own messaging agenda.Burford only attempted to deploy such a counter narrative in the ‘concluding remark’. The company declared short sellers to be “a fundamental menace to an orderly market and to the value inherent in long-term investing”. But this was a tired and unimaginative cliche. It invited the standard response from all activist campaigns which presented the attackers, not the targets, as the champions of true value and shareholder interests by ‘revealing’ reality. In response to Burford’s remark in an article in the Financial Times on August 9th, Muddy Waters’ founder Carson Block was simply able to state, “Over the medium-to-long-term, if the activist is wrong, the company is not going to stay in the dirt.” ⁱThe company also rested on its announcement and failed to deploy media assets as effectively as its attacker. On the morning of the release Carson Block was being interviewed on the BBC’s Today Programme, giving a human voice to the narratives in his attack.

Response 2 - ‘spoofing and layering’

On 12th August Burford made a statement. This suggested the magnitude of its share price fall had been the result of illegal trading activity. Most crucially, it introduced this through a compelling, evidence-backed concept that successfully carried its argument to media and generated sustained coverage.Burford claimed it had found evidence of ‘spoofing and layering’ in trading activity around the time of the Muddy Waters attack. These tactics can drive the price of a stock lower artificially but depend on capabilities associated with the opaque world of high frequency trading by complex ‘black box’ computer algorithms.Whether intentional or not, ‘spoofing and layering’ created an effective counter narrative. It tapped into embedded media and public fascination with the esoteric, ‘secret world’ that hedge funds are perceived to inhabit. More importantly, it cast Muddy Waters as merely another player in that narrative and in that opaque world.In terms of narrative construction the move was fast and insightful. Even the term ‘spoofing and layering’ provided an effective shorthand description of an alternative cause for the company’s crisis. This narrative is still discussed intact by journalists a year later.

Figure 2: ‘Spoofing and Layering’ counter narrative - potential to escape ‘checkmate’

But Burford insisted on using this as the premise for challenging the attack in court. The subsequent legal battle would be played out in media over nearly a year. The coverage would lock the company into a newscycle that simply churned the clear narratives in the original attack.The court case meant Muddy Waters’ core ‘negative’ arguments around corporate governance, valuation and accounting were repeated again and again. Burford’s legal counter argument simply provided the opposing, ‘positive’ material needed to complete that story circuit. Burford’s strategy had simply created a self contained narrative ‘battery’ which would only run down upon the case’s conclusion, and that would be dependent on a third party.

Figure 3: Burford’s insistence on a legal battle created a ‘narrative battery’, locking the company into a newscycle that churned over the narratives in the original attack for nearly a year.

Reponse 3 - employee movements and valuation reporting

On 15th August Burford took steps to address directly the criticisms made by Muddy Waters. The company replaced the wife of the CEO as finance director and two long-sitting board members. But these actions were prescribed by the attack and operated within the communications checkmate. This meant they provided opportunities for simple, effective bite-sized repostes from Muddy Waters.

“It is clear from this that Burford is more interested in imposing fig leaves than real guard rails ... This seems more a question of who would do the job and who wasn’t married to the CEO.”

- Carson Block ⁱ

On 23rd September the company also released a report explaining how it valued its investments. One analyst at a firm acting as broker to Burford said the company’s fair value changes had been “directionally correct”, referring to the way in which they were marked up or down. ⁱBut even this report created debate and aspects of valuation remained perceived as unclear. The media still focussed specifically on the value of single large cases. Analysts continued to criticise Burford for not declaring the value given to the ‘Petersen case’ on the company’s balance sheet. One analyst commented, “Burford makes a virtue of being transparent but they won’t disclose what value is being held at, and we don’t understand why.” ⁱReplacing its finance director and two board members may have been necessities. The same can be said of the investment valuation report. But these actions were prescribed by the Muddy Waters attack and still operated within the constraints of its narrative network.Ultimately there was insufficient messaging activity and content released about anything from Burford other than the crisis. The company had not allocated communications resources to developing an adequate investor-focussed value narrative over the years, and its advisers had not identified the right media to carry that narrative.

What should have been done differently?

Investors should have been recognised as a unique audience requiring specific attention.

At the start of Burford’s journey, prospective media outreach should have focussed on the media and journalists that investors actually valued. A Rebbelith analysis of Burford’s key shareholders in the summer of 2019 revealed:

There were 63 individual publications and journalists that had proven value to those asset managers.

Figure 4: Mapping the media landscape - Modern capabilities would have allowed Burford to focus on media and journalists that their investors actually valued.

Of those identified, 20 had the most value. Messages or content carried by these titles and individuals would have had a measurable impact on investors and removed guesswork by communications advisers looking for media to target.

Figure 4 (continued)

This insight could also have been used to target content at any individual asset manager/investor, both to raise new assets or retain existing allocations.

Figure 5: Identifying valued media at a granular level of detail - where to focus attention to reach specific investors.

Narrative opportunities and vulnerabilities in valued media should have been identified, mapped and monitored.

These media should then have been analysed both in the past and continuously with respect to Burford’s key investor messages and core competencies. This would have revealed the location, structure and and progression of:

Narrative opportunities - What content, interviews or campaigns could Burford have created to maximise the potential of those opportunities?

Narrative vulnerabilities - How were Burford’s vulnerabilities perceived and covered in the media most valued by their key investors? What content or campaigns could have been deployed to change those perceptions?

A narrative analysis conducted on the company’s share performance and profitability during its long bull run would have revealed three core narrative vulnerabilities. These focussed on unrealised gains, returns metrics and single large cases:

Figure 6: Identifying and visualising narrative vulnerabilities.

Crisis responses should have taken into account the company’s narrative network and identified any potential for a narrative ‘entanglement’

A data-backed, visual model of a company’s narrative network would have:

Exposed ‘unknown unknowns’ and improved understanding of known vulnerabilities.

Provided an intuitive understanding of the depth, context and velocity of the crisis and guided allocation of communications resources for maximum impact.

Figure 7: Mapping and navigating narrative networks before they become narrative entanglements

Allowed a truly responsive, agile communications strategy to be deployed, utilising the experience of the company’s reputation and communications experts fully.

Allowed the company to measure response successes with media and investor audiences.

Valued media models would have allowed:

Response messages to be targeted at titles and journalists that had the most reach with investors during the crisis.

Titles and journalists to be assessed against their value to investors if they were a) carrying harmful content:

Figure 8: Locating titles carrying harmful messages and content, and mapping their reach

or b) closely integrated with the threatening campaign’s information networks:

Figure 9: Visualising the reach of potentially harmful organisations, campaigns and messages

Harmful media could have been identified quickly and bypassed in favour of other valued titles.

Figure 10: Mapping media reach to key stakeholders and bypassing harmful messages in certain titles.

Lessons

Muddy Waters deployed a very sophisticated communications campaign. Its impact was so high for three core reasons:

It identified and activated narratives surrounding Burford to create a coordinated ‘narrative entanglement’ and ‘communications checkmate’.

Its architects had a detailed, modern understanding of how information flows between and within groups of stakeholders. They ‘primed’ those networks and then ‘pulsed’ varied information within them to keep the attack fresh.

Burford’s communications advisers and publicity agents deployed planning, monitoring and crisis response techniques that are now redundant.

Every organisation, campaign or brand is embedded within a narrative network.

Figure 11: Brand reach constituents for major international retailer.

Whatever the industry, that network, can be manipulated to create a narrative entanglement, putting a company’s goals, future and reputation at risk.

Figure 12: Brand reach narrative development for major international retailer (February - May 2019)

Burford is not alone and this phenomenon is not unique to investing or public companies.But these narrative and stakeholder networks often contain phenomenal opportunities for reaching key stakeholders and for commanding the media conversations that really matter.

Figure 13: Narrative potential in the video games industry.

With adequate awareness, analysis and an appropriate strategy, these narrative networks can be identified, understood and, crucially, navigated. Like the original ocean maps from which we draw our heritage, we believe this is best done with a Rebbelith, but one fit for plotting a course through the modern media.

Thank you

We will be in contact shortly.In the meantime, why not have a look at our brochure?